click

images fullscreen

< > 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Pulmonary Space

In his system of art, the 19th-century German philosopher, G. W. F Hegel, considered music the purest and most beautiful of art forms, as opposed to architecture, which he relegated to the lowest rung, viewing it as an imperfect art, impure and poor. The criteria at stake in this hierarchical classification stems from each art form’s relationship to its materiality, situated between dependence and liberty. For Hegel, the more an art form went beyond its materiality, the less it was constrained by the natural world, the closer it was to the pure spirit, weightless and transparent, the more elevated, transcendent and beautiful it became. Poetry and music, the two art forms he considered superior, were precisely those that at first glance most pointedly broke free from their materiality. Music is no more than waves, and poetry no more than words. In contrast, architecture or sculpture are completely entrenched in their base materiality, of rain, weightiness and heavy and opaque materials which are sculpted or built with pain and suffering.

If this classification of art – suspended between base materialism and transcendence, heaviness and lightness, opacity and clarity, fullness and emptiness, earth and sky, is perfectly rational from both a poetic and pre-scientific perspective – then today it has become completely obsolete, according to Hegel’s own criteria, taking into account what scientific progress in the domain of physics, chemistry and biology has brought to our knowledge of the void, waves and the air.

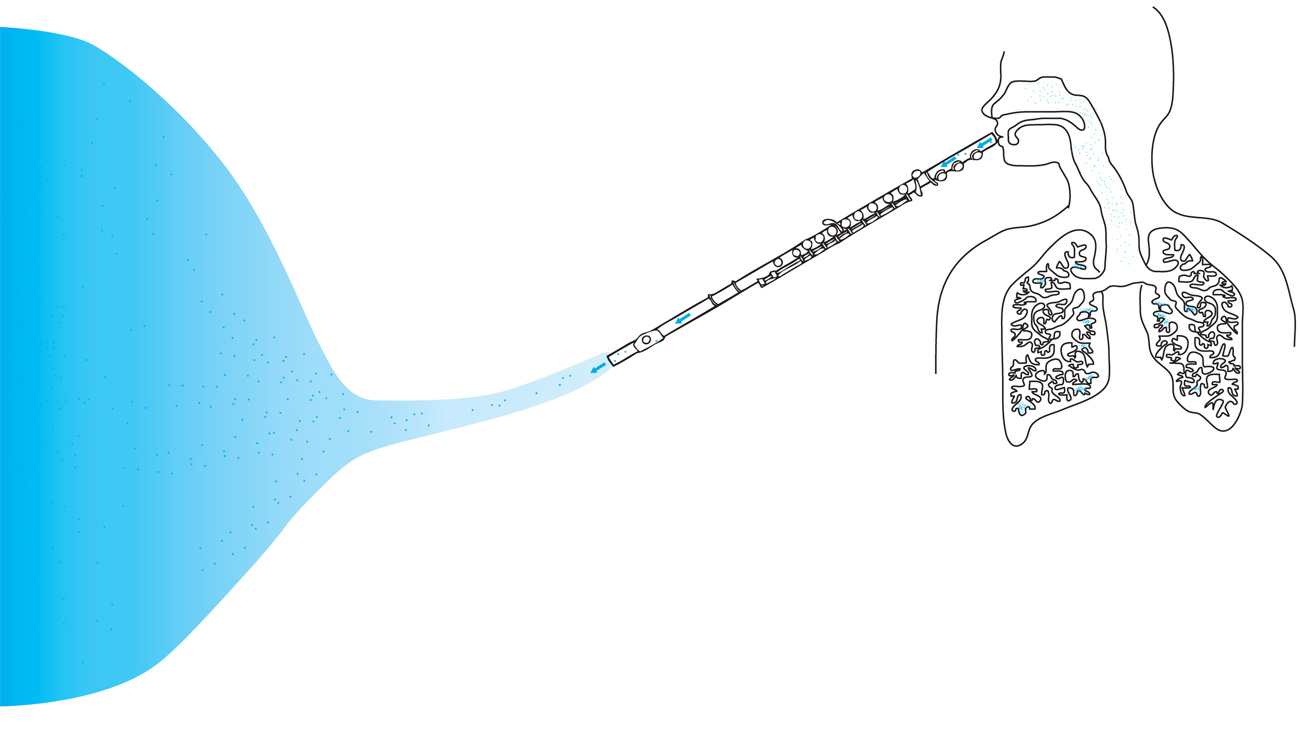

What we know today is that sound or voice are not abstract or dematerialised, even though they are ethereal and invisible, they are no more transcendent than a stone or soil, and they most certainly do possess a physical, chemical and biological dimension. The physical dimension of sound is a tangible mutation of air according to a specific wave length. It is a pressure point placed upon the air in a defined space. It is a bodily temperature of close to 37˚ Celsius that the lungs subsequently transmit into the air as a result of breathing. The chemical dimension of the voice is made up of a gaseous content, measurable by the amount of oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, rare gases and water in the form of vapour that is amassed in the air with each and every breath. Music and poetry both have a biological dimension, made up of pollen, micro-organisms, germs hanging in the air, bacteria and viruses. Louis Pasteur, who made this discovery in 1878, insisted that all those close to him place a handkerchief over their mouths whenever they passed a hospital.

It is this lack of thought of Hegelian aesthetics that we are proposing to feed into our project, Pulmonary Space, at the Barbican. Our project is one of densification of the imagined immateriality of music, an accumulated phenomenon, a condensation of sound that reveals itself as visceral and humid. Our project accepts that sound is not a pure and abstract vibration but moreover a warm tide of germs and perspiration that flows from our mouths into the air and imperceptibly transforms our physical and chemical world.

Can wind quintets carry and spread the flu virus? Can we feel the humidity of the singers’ breaths, which rise in the air whilst the choir’s song augments? Do we inhale the breath of the trumpeter while he plays? Which part of the music is chemical? Does not music, with its waves, physical impressions on the air and distillation of vapour, begin to take on an architectural form? An invisible yet perfectly audible form. And if we accept that music is not abstract but actually produces a volumetric space. Can’t we finally accept once and for all what music really is, namely not a void, hollow and immaterial but rather material, albeit very light and impalpable, but still humid, dense, physical and chemical?

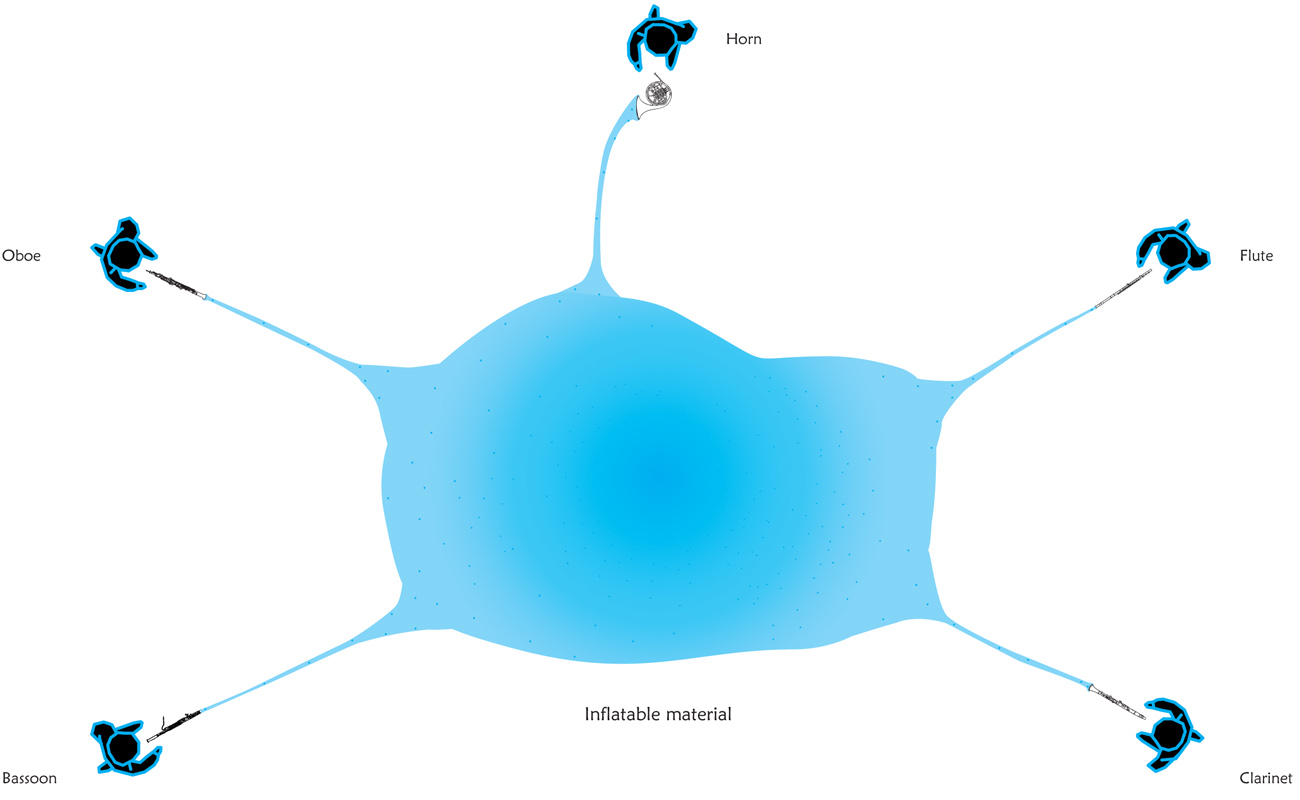

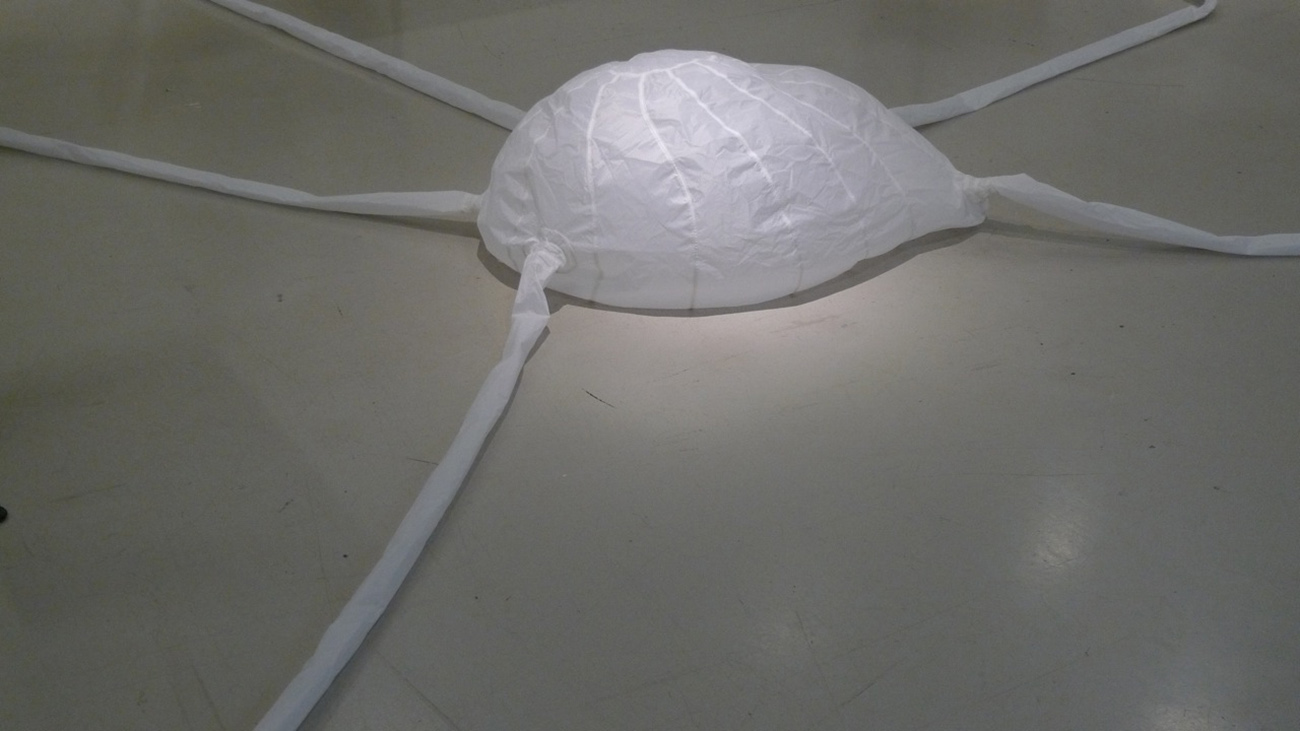

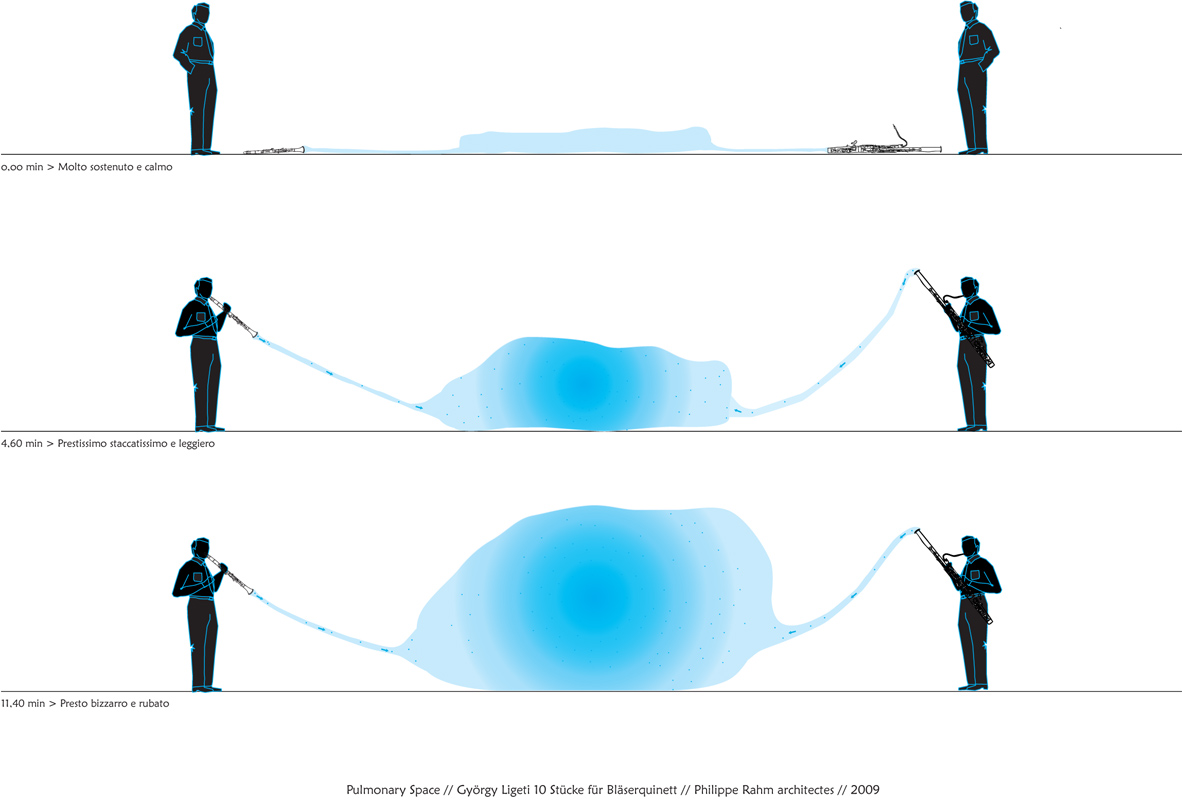

In reality it is this physical densification of music, which loses its transcendental and abstract quality that is already at play in the work of Ligeti. In the 1960s he defined his music with terms such as ‘very dense musical fabric’, ‘static’, ‘viscous’, ‘sonic textures’, ‘sonic spaces’, ‘acoustic immobility’. Here, music becomes physically present, takes up space, pushes, swells, occupies, expands, and undergoes a process of densification until it completely inhabits the space, literally transforming it. Ligeti invokes this materiality of music, this physicality of sound waves, both sensorially and sensually through his confirmation that he feels, for example, the weight of a sonic block, that a sonic scape fills up its surrounding space and dilates just like when we blow up a balloon. In a childhood dream, he envisaged sonic layers creating different textures much like a spider’s web, the web representing its totality and the threads the building blocks. Music is no longer abstract, no longer simply a temporal musical line, constructed according to thematic developments or rotations between acoustic and non-acoustic moments. On the contrary, it is a sonic mass, heavy, physical, abundant, as Ligeti defines it: ‘a continuous event, static clusters, a perpetual oscillation, without stops, comparable to the air’. But it also has a physical manifestation, ‘the movement of a breath: the crescendo of a breath that escapes and subsequently wilts’.

Our project for the Barbican consists of a semi spatial construction. The materials of the space are no longer those of the natural world: air and heat, pure elements from an original state. It is a new nature that we are creating, a new atmosphere, brought forth from culture. But it is a culture with no transcendence. The music becomes viscous, fetid, humid, excised from the lungs and in turn inhaled. Space assumes an architectural form of breath in which the listener is immersed. Music is no longer simply heard but breathes, inhales and constructs its own space.

team

Philippe Rahm architecteslocation, date

"Radical Nature" exhibition curated by Francesco Manacorda, Barbican Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom, 2009^